On a heading the Shell: final images for exhibition

One photograph from each walking circle site was selected for printing and exhibition.

From each walking circle site, photos were taken on a compass bearing to the Shell Chimney.

- Big Rock

- Lara RSL

- Limeburners Lagoon

- Moorpanyul Park

- Steampacket Gardens

- Barwon River Rowing Precinct

- Bellarine Rail Trail Christies Road

- Drysdale Station

- Swan Bay

- Point Lonsdale

- Ocean Grove Surf Beach

- Barwon Heads

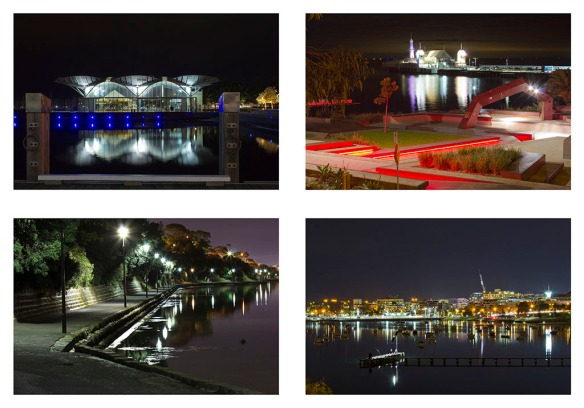

The Night Walk: The final exhibition images

Here are the 10 photos that were printed for exhibition.

- Shell Refinery from Limeburners Lagoon

- The Cracker, Shell Refinery

- Phosphate Works, North Shore

- Barrett Burston Maltworks

- Barrett Burston Maltworks

- The Bay Trail from Griffin Gully

- Cityscape from Drumcondra

- Cunningham Pier and the Skate Park

- The Carousel

- Looking towards Flinders Peak from Steampacket Gardens

M~M Exhibition: Night Photos, Shell heading photos and a big collage

Three of the works for the Mountain to Mouth creative response are now on display outside the Visual Arts office, at Deakin’s Waterfront Campus, until at least August 9th. Opening hours are 8:30 to 5:30 weekdays.

Walk this Land – M~M creative response

Walk this land – afternoon, evening and night.

Walk this land – dawning light

Driving rain – sun and pain

Walk this land – river to ocean, mountain to sea

Walk this land – forest, farm and footsteps

Sun above, land beneath, waves beside

Walk this land, evening light, shining night

Fire on ocean

Helen Lyth, Walk this land, 2014, Mixed media

Creative response part 3.

Should public money be spent for art events?

” So long as my Tax wasn’t wasted on this party of earth worshipers! With Council racking up record debt!” [1]

Here today, gone tomorrow: Should public money be used to support ephemeral arts events?

At 10:30am on Friday, 9th May, 2014, with bicycle and touring trailer I was one of the first to arrive at Big Rock in the You Yangs for Mountain to Mouth: Geelong’s Extreme Arts Walk. By 8pm, on Saturday, May 10th, it was all over. A week later, the fury began, with vitriolic comments online and in the Geelong Advertiser’s letters column following an opinion piece by Michael Martinez, CEO of Diversitat (a multi-cultural organisation which oversaw Geelong After Dark, an associated event).[2] On May 28th, the Geelong Advertiser published an article by reporter Mandy Squires, under the headline, “City’s Mountain to Mouth walk and arts festival proves costly”. Squires used emotive language like “(COGG) forked out $119,000 and Geelong Major Events (a council committee) $50,000” and “…Mountain to Mouth walk and After Dark arts festival has set the council back about $170,000.”[3]

Surprisingly, from the beginning, the local daily paper, News Limited’s The Geelong Advertiser, had been lukewarm to this major local event, with little pre-event coverage. One small picture and a short article were all to be seen in the paper on Saturday 10th May. [4] This was despite the fact that Kaz Paton, Manager of the Arts and Culture department at the City of Greater Geelong, had met with the Advertiser’s editor long before the event and gained the promise of support.[5]

Why is it that a modest outlay of public money on an arts event often garners an extreme negative reaction from some community members and media? Should public money be spent to foster the arts, and, in particular events which are, by their very nature, transitory – ephemeral? Is there any benefit from public arts events? I shall use the example of Geelong’s Mountain to Mouth in order to attempt to answer these questions.

Mountain to Mouth had its genesis at least ten years ago when Geelong took part in an community arts program called Generations.[6] The purpose was to address community needs within specific municipalities. Geelong’s project was called Connecting Identities. The aim was to address the rapid change which Geelong was (and still is) undergoing.

With Meme McDonald as Artistic Director, the project developed into a community event, titled Mouth to Mountain, which was held in 2009. This was a journey (run as a relay with multiple forms of transport) across the municipality from Barwon Heads in the south to the You Yangs in the north. Various ceremonies and arts installations were set along the event which culminated with a ceremony and concert at Big Rock in the You Yangs.[7]

Feedback from participants and spectators was overwhelmingly positive, with, specifically, spectators wishing to be involved as active participants in the journey. The Arts and Culture Department therefore sought funding from Council for a second event, with the view to this becoming a regular arts event.

Meme McDonald was once again appointed as Artistic Director. It was decided to make the event a twenty-four hour walk, with ceremonies and art installations along the way.[8] The walk would pause in the Geelong central business district overnight, where an ancillary arts event, Geelong After Dark, was to be held.[9] [10]

Local artists garnered the support of their communities to produce art works in twelve sites along the walk. These would provide short resting places and the opportunity for walkers to view and participate in ‘extreme art’. Artists and performers were also commissioned to produce works, theatre and music for Geelong After Dark. To add festivity to the parade and acknowledge the twelve council wards, twelve flags were carried on the walk by a rotation of community flag ambassadors. A key facet of the event was Canoe, an art work which was to be carried with the walk as a vessel for water and fire, set alight at the closing ceremony at Barwon Heads before being carried out to sea with the evening tide .[11]

There was a large amount of community involvement in the making of the art works. While final figures are not yet complete, to date it is estimated that there were 1760 volunteers involved. Most of these worked with the artists to make objects for the art sites along the way. There were also participants in a community choir and other artists performing at Geelong After Dark, as well as helpers with site set up and management. [12]

Around 550 participants registered for the walk, many walking a large part of the entirety of the eighty kilometre route. As well as this there were around 300 spectators at the Big Rock starting ceremony, and over 2,500 at the final ceremony at Barwon Heads. This does not include over 400 flag and canoe ambassadors. [13] Geelong Councillors and elders from various multi-cultural communities participated in ceremonies at Big Rock, Steampacket Gardens and Barwon Heads.

Luisa LaFornara (Producer of Geelong After Dark) reported that because of the free, ‘pop-up’ multi-venue nature of Geelong After Dark, it was difficult to gauge actual numbers. However, several thousands of people were estimated to have attended.[14] This included around 1000 viewing projections on the Wool Museum, 450 attending GPAC, and 400 people braving the May cold and wind to attend the rooftop cinema.

Conservatively, more than five thousand people were involved in one way or another with the dual event. From these participants, the feedback has been overwhelmingly positive.[15] Individuals had their own highlights of the event. For some, the canoe’s final journey, set alight and drifting out into the night on the outgoing tide was overwhelming. For others, the achievement was achieving a physical challenge. Others relished finding new places around their extended city, or the delight of the divers walking circles and their inspiring and transitory art.

Financially, from a minuscule budget of $210,000 for such a major event, the economic impact of the project was conservatively put at over $1,000,000.[16]

I interviewed some of those closely involved with Mountain to Mouth. Zoe Ennis, who was Operations Manager, in charge of the logistics of the event, was troubleshooting and leading the event by bicycle. A highlight from her point of view was:

… when it was all calm, there wasn’t a gate to open or a road to cross, on the Bellarine or other parts. It was just listening to people talking behind us and having a good time. …It’s just picking up on little things – people making friends, or realising they knew people or just chatting was really nice too.[17]

Similarly, Kaz Paton, producer, walked several sections of the event. She talked to people about their experience. She also escorted Geelong’s mayor to some of the events in Geelong After Dark, finding both his, and the public’s response excitement and delight. [18]

Esther Oakes was the artist responsible for the Moorpanyul Park walking circle- which was one of the night installations. She found people taking the time to look closely at the lantern-lit hyperbolic crochet and other features, really experiencing the work. She, herself, was delighted when darkness came and her concept was not just realised, but spellbinding.[19]

The overwhelmingly positive feedback from those who experienced Mountain to Mouth shows, that, for this city, at this time of change and uncertainty, there is a positive result for using public funds to finance public arts events, even if there is no permanent art object resulting. Indeed, from pre-history it can be seen that public ceremonies and expressions of creativity have been used to bind communities, consolidate customs and religion, and educate people in the places and stories that go to make up societies.[20] There is a lasting impression left by public art events. However, that impression is not a physical entity, but a shared memory of the people who participate.

Art cannot be measured only by collectability. Indeed, the concept of permanency and collectability is a relatively recent, Western phenomenon.[21] Alongside the contemporary trend for art as a tradeable commodity, runs a much stronger and permanent thread that art’s purpose is to enhance our lives, strengthen our communities and explain and comment upon our world. It therefore becomes not just desirable, but essential, for communities to fund arts events for the ongoing growth and health of society.

Appendix 1

Post-event statistics (not yet complete) – presented by Duncan Esler at final Production Meeting 4th July, 2014

Event statistics – Duncan (as outlined in final Production meeting, July 4th, 2014)

Some figures from District Coordinators and Bron still to come.

- Unpaid work – 1760 volunteers – participating – making e.g. lantern making

- Around 5200 hours of work into the project (unpaid and paid)

- Spectators to M~M (not GAD) – will increase – 5500 – at sites – some figures outstanding

(the real power is in the community volunteering and participating – not the actual walkers or spectators)

- Over $1,000,000 of economic input from the project (conservative figure)

Anonymous (2014), ‘Panem et Circenses (Bread and Circuses)’, <http://www.capitolium.org/eng/imperatori/circenses.htm>, accessed 17/7/14.

Purpura, Allyson (2009), ‘Framing the Ephemeral’, Introduction to a special issue: Ephemeral Arts I, 42 (3), 11-15.

[1] Realist of Geelong, online comment, in Geelong Advertiser online, posted 15th May, 2014 http://www.geelongadvertiser.com.au/news/opinion/arts-event-proves-a-journey-of-discovery-in-more-ways-than-one/comments-fnjuhr1j-1226918781143

[2] Michael Martinez, Arts event proves a journey of discovery in more ways than one, The Geelong Advertiser, p. 11, May 15th, 2014 also published online, retrieved 12/7/14 http://www.geelongadvertiser.com.au/news/opinion/arts-event-proves-a-journey-of-discovery-in-more-ways-than-one/comments-fnjuhr1j-1226918781143

[3] Mandy Squires, City’s Mountain to Mouth walk and arts festival proves costly, The Geelong Advertiser, p. 12, May 28th, 2014. Online version retrieved 12th July 2014, http://www.geelongadvertiser.com.au/news/geelong/citys-mountain-to-mouth-walk-and-arts-festival-proves-costly/story-fnjuhovy-1226934134358

[4] Putting this into context, for any large community sporting event, fun run, marathon, etc. and for events like the Celtic Festival, The Geelong Advertiser‘s policy is to present a 4, 8 or 16 page post-event insert featuring pictures, names and commentary.

[5] Kaz Paton, Interview with Helen Lyth, 2nd July, 2014, Helen’s Journey (private online blog) – https://walktowater2014.wordpress.com/interview-with-kaz-paton/

[6] Cultural Development Network, The Generations Project, n.d., retrieved 12 July, 2014, http://www.culturaldevelopment.net.au/projects/generations-2/

[7] Kaz Paton, Interviewed by Helen Lyth, 2nd July, 2014, Helen’s Journey (private online blog) – https://walktowater2014.wordpress.com/interview-with-kaz-paton/

[8] Meme McDonald, Interviewed by Helen Lyth, May 28th, 2014, Helen’s Journey (private online blog), https://walktowater2014.wordpress.com/interview-with-meme-mcdonald-artistic-director/

[9] Kaz Paton, Interviewed by Helen Lyth, 2nd July, 2014, Helen’s Journey (private online blog) – https://walktowater2014.wordpress.com/interview-with-kaz-paton/

[10] For a more detailed background and description of Mountain to Mouth 2014 see

Helen Lyth, History and Background to Mountain to Mouth, Mountain to Mouth 2014-Helen’s Journey, https://walktowater2014.wordpress.com/2014/07/17/history-and-background-of-mountain-to-mouth/

[11] Meme McDonald, Interviewed by Helen Lyth, May 28th, 2014, Helen’s Journey (private online blog), https://walktowater2014.wordpress.com/interview-with-meme-mcdonald-artistic-director/

[12] Duncan Esler, “Event Statistics”, Minutes of M~M Production Team Final Meeting, Friday, July 4th, 2014, retrieved 17/7/14. https://walktowater2014.wordpress.com/meeting-notes/ reprinted here as Appendix 1.

[13] Duncan Esler, Interview with Helen Lyth, 18th June, 2014, retrieved 17/7/14 https://walktowater2014.wordpress.com/interview-with-duncan-esler-production-manager/

[14] Luisa LaFornara, “Geelong After Dark Report”, Minutes of M~M Production Team Final Meeting, Friday, July 4th, 2014, retrieved 17/7/14. https://walktowater2014.wordpress.com/meeting-notes/

[15] A post-event survey was part of the Connecting Memory ap. Due to issues with few people accessing this download, only about 30 surveys were returned. However, there was a lot of feedback via emails, and by word of mouth to the organisers and city – overwhelmingly positive. From participants, the small amount of negative feedback was about the speed of the walk (too fast for some), and the timing which meant walkers were arriving in the city when Geelong After Dark was ending making it impossible for them to participate in both events. Other negative feedback was largely from non-participants, who read press coverage in the Geelong Advertiser – and concerned the cost to the city for this event.

[16] Duncan Esler, “Event Statistics”, Minutes of M~M Production Team Final Meeting, Friday, July 4th, 2014, retrieved 17/7/14. https://walktowater2014.wordpress.com/meeting-notes/ reprinted here as Appendix 1.

[17] Zoe Ennis, Interviewed by Helen Lyth, 18th June, 2014, retrieved 17/7/14, https://walktowater2014.wordpress.com/interview-with-zoe-ennis-operations-manager/

[18] Kaz Paton, Interviewed by Helen Lyth, 2nd July, 2014, Helen’s Journey (private online blog) – https://walktowater2014.wordpress.com/interview-with-kaz-paton/

[19] Esther Konings-Oakes, Interviewed by Helen Lyth, Thursday, July 4th, 2014, retrieved 17/7/14, https://walktowater2014.wordpress.com/esther-konings-oakes-district-coordinator/

[20] An example of this comes from the classical tradition. Indeed, Juvenel, a Roman poet and satirist of the late first century, cynically coined the term ‘panem et circenses’ (bread and circuses) to describe how a political regime can keep the public happy.

Panem et Circenses, Capitoleum.org, n.d., http://www.capitolium.org/eng/imperatori/circenses.htm, retrieved 17th, July, 2014.

[21] Allyson Purpura, ‘Framing the Ephemeral’, Introduction to a special issue: Ephemeral Arts I, 42/3 (09// 2009), 11-15.

History and Background to Mountain to Mouth

Mountain to Mount had its genesis at least ten years ago. In around 2002, the City of Greater Geelong (amalgamated from 6 municipalities around Geelong and the Bellarine Peninsula by the Kennett Liberal Government in 1993)recognised the need for a specific department of Arts and Culture. Kaz Paton was appointed coordinator, and later manager. This fledgling department took over responsibility for the Potato Shed, the Wool Museum, and Heritage Centre and funding for the Gallery and libraries. When interviewed, Kaz Paton added, ” We also felt that we really needed to demonstrate to the organisation and to our councillors, the power of the art.” [1]

At this time, Geelong, along with other municipalities around Australia, was invited by The Cultural Development Network to take part in a program called Generations.[2] Generations provided funding and support for municipalities to address needs within their communities through the arts. “It was a project see how the arts could impact on key big issues in communities. “[3] At that time, as now, Geelong was going through a process of rapid change. It was decided to produce an event with the aim of uniting the community with a sense of pride and common purpose. The title Connecting Identities was coined, and Meme McDonald appointed Artistic Director. Meme devised the first Mouth to Mountains project, which, in 2009, ran as a relay bringing water from the mouth of the Barwon River up to the You Yangs.[4] There were many legs on the relay, and twelve participants in each stage. The mode of transport varied from kayaks to horses, to parents pushing prams, to story tellers travelling by train, to cyclists, Ford vintage cars, and artists. At each change-over place, there were festivities (for example at Johnstone Park, the mayor abseiled from the roof of City Hall).

CoGG Mayor abseiling from City Hall, MtoM 1009. Photo from MtoM website, http://www.geelongaustralia.com.au/connectingidentities/mouthtomountain/

At Big Rock, there was a ceremony, and, with the falling of night, an open air concert where community groups and artists performed music written specifically for the event.[5]

Big Rock final ceremony 2009 MtoM Photo from MtoM website http://www.geelongaustralia.com.au/connectingidentities/mouthtomountain/

The feedback from this first MtoM was immense. In particular, those who attended or participated asked for an event in which they, themselves could participate more fully.

With the Generations program wound up, there was no new outside funding to provide a second cultural event. What seemed a very modest allocation was made in the 2013 to 2014 city budget and Meme McDonald was once again invited to be Artistic Director. A production team was formed. This included representatives from two key community groups partners, Karingal[6], a charity organisation, who would oversee the registration process, and Diversitat[7] (a multi-cultural organisation with experience in running large scale community events) who developed Geelong After Dark. Geelong After Dark is a multi-site arts pop-up festival of projections, music, performance and visual arts around the central business district on the first night of M~M. Deakin University was also a partner, providing research on the success, or otherwise, of the event, academics as canoe carriers, and student participation producing art work for Geelong After Dark and interns to work on the project itself.

With very little funding, and little support from the local print media, promotion went ‘underground’ – subversive in a similar way to the subversiveness of the ephemeral nature of the art of Dada in the early twentieth century.[8] The city and Diversitat developed Facebook sites for M~M and Geelong After Dark, and these became vital promotion and information tools as the event neared.

Twelve months before the event, local artists were invited to express interest in working to produce art works and to manage the twelve static sites which would become the ‘walking circles’. These were arts sites – ceremony sites at the beginning and end of the marathon walk, and ten other resting places, where the walkers would pause to walk an especially designed labyrinth and partake of the works of local artists and community groups. The walkers walked into the labyrinth to some special feature in the centre and then out again, to continue on their pilgrimage to Barwon Heads. Each of the site coordinators sought community involvement to produce the walking circle installations, and to provide services (like food) for the walkers. For example, the third circle at Moorpanyul Park in North Shore was managed by local resident and artist Esther Konings-Oakes. Esther worked at schools, community events and with local groups (like the Yarn Bombers Group), to produce hundreds of fish lanterns, illuminated hyperbolic crotched sculpture, and porcelain oyster shells for the nocturnal walking circle. A local neighbourhood house, which has a training cafe, provided a food tent.[9]

This community involvement prior to the event was the case for most of the sites. In all, thousands of members of the community contributed.[10]

Ben Gilbert, a sculptor, was commissioned to produce “Canoe”, a symbolic boat on wheels, which led the walkers’ procession as they travelled the eighty-four kilometres from Big Rock to Barwon Heads.

Figure 1 Canoe, carried by CFA members, begins the long journey from Big Rock to Barwon Heads

Figure 1 Canoe, carried by CFA members, begins the long journey from Big Rock to Barwon Heads

Another artist, Kathryn Williams, who works in textiles, designed and made twelve silk flags (one for each council ward).

Figure 2 Flag ambassadors lead the procession near theYou Yangs Visitors’ Centre

Figure 2 Flag ambassadors lead the procession near theYou Yangs Visitors’ Centre

These flags were carried by community ambassadors, selected by the twelve ward councillors. Behind Canoe and the flag bearers, registered participants walked. Some walked the entire eighty-four kilometres. Others only walked one or two sections. All the proceeds of the modest participation fee went to support Karingal’s work revegetating the environment. [11]

[1] Kaz Paton, Interviewed by Helen Lyth, 2nd July, 2014, Helen’s Journey (private online blog) – https://walktowater2014.wordpress.com/interview-with-kaz-paton/

[2]Cultural Development Network, The Generations Project, n.d., retrieved 12 July, 2014, http://www.culturaldevelopment.net.au/projects/generations-2/

[3] Meme McDonald, Interviewed by Helen Lyth, May 28th, 2014, Helen’s Journey (private online blog), https://walktowater2014.wordpress.com/interview-with-meme-mcdonald-artistic-director/

[4] More information, Connecting Identities website http://www.geelongaustralia.com.au/connectingidentities/about.html

[5] I was lucky enough to be a participant – organiser and leader of the bike leg, and, as secretary of the Geelong Chorale, a convenor and participant in the final concert.

[6] More information about Karingal at http://www.karingal.org.au/

[7] More information about Diversitat at http://www.diversitat.org.au/

[8] Purpura, Allyson , ‘Framing the Ephemeral’, Introduction to a special issue: Ephemeral Arts I, African Arts 42 (3), (2009) 11-15.

[9] Esther Konings-Oakes, Interviewed by Helen Lyth, July 3rd, 2014, Helen’s Journey (private online blog), https://walktowater2014.wordpress.com/esther-konings-oakes-district-coordinator/

[10] According to current figures from CoGG, which are not yet complete, 1760 volunteers worked prior to the event and on the days of it.

Duncan Esler, M~M participation statistics, final M~M Production Meeting, Friday, July 4th, Appendix 1.

[11] Duncan Esler, Interviewed by Helen Lyth, 18th June, 2014, retrieved July 17th, 2014 https://walktowater2014.wordpress.com/interview-with-duncan-esler-production-manager/

Framing the Ephemeral

Purpura, Allyson (2009), ‘Framing the Ephemeral’, Introduction to a special issue: Ephemeral Arts I, African Arts, 42 (3), 11-15.

- Intro. To a set of articles about ephemeral art in the publication above. http://eds.a.ebscohost.com.ezproxy-f.deakin.edu.au/eds/detail?sid=b362fdf3-2797-40cb-9960-b32c27967f83%40sessionmgr4001&vid=1&hid=4202&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWRzLWxpdmUmc2NvcGU9c2l0ZQ%3d%3d#db=hus&AN=505264753 for the other articles in the publication.

- Def. Ephemeral art – ‘ephemeral art refers to works whose materials are chosen by the artist or maker for their inherently unstable characteristics, or which are created with the intention of having a finite “life.”’ P.11

- Can’t be ‘collected’ – so no long term purpose – like gallery or trading

- defies conventional expectations around the preservation, display,

- and commodification of art and confounds the museum’s mission to preserve works in perpetuity. P.11

- cites work of S. African Willem Boshoff – 2005 – fine sand, stencilled onto gallery floor – comment on degradation of languages of Africa. As an 8 month installation – the gallery staff needed to maintain the exhibit, although the intention of the artist was it’s degradation over time. 11

- Other such gallery works are those painted directly onto walls of galleries – and removed with the closure of a specific exhibition. 11/12

History of the ephemeral

- From 18th century – permanence of art became important – scepticism about art that was not durable – this driven by the increasing importance of collection/ownership/art as commodity. ‘It was a period in which objects became “art” for all time, and public museuims their custodians’ 12

- Cites ‘Baudelaire’s clarion call to embrace the transience of beauty and flux of the modern city – “the ephemeral, the fugitive, the contingent, the half of art whose other half is the eternal, the immutable”. Says this was ‘silenced by the museums of his day. 12

- This permanence in art is a western concept – non-western cultures ‘accept transience not only as a fact of life, but also as a path to ensure well-being in this world, as well as the next.’ 12

- Cites Hindu rice flour paintings in India, also African performance art pieces like masks and figures. The intent was for natural degradation of these (sometimes such degradation was spiritual – a degradation of the evil spirits they might contain) – but this is interrupted when museums and galleries collect and preserve these artefacts. 12

- Early 20th century – a move among Western artists – Dadaism towards questioning of art – and especially the concept of enshrining art pieces – ‘ephemeral art came to be viewed as subversive, or, at best, recalcitrant art form.’ “Dada sound and visual artists hailed the immediacy of the sense and embraced transience as a way to amplify a present that was being ravaged, in their view, by the nonsensical violence and conceit of nations at war” 12

- Ephemeral art allows artists to “visualize time and memory as active, if not political, dimensions of the work (in distinction to the “time-based media” of film, video, and audio recordings, in which the work unfolds and is experienced over time).” 13

- Cites

o Columbian artist Oscar Munoz – water painting of face on hot concrete – evaporating before the face is ever completed – faces of the dead which disappear – about political disappearances in repressive regimes. 13

o Juchen and Esther Gerz – counter monument for the holocaust (Germany)13

o ‘And though Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta brought closure to her ephemeral works by documenting them on film, she did so in an ironic way. In her Silueta series (1973–1980), the artist laid her body down in flowerbeds, mud, sand, and snow and photographed the temporary impressions it left behind; but in these images, now the collectable dimension of her work, it is her very absence that endures (Nardella 2007; see also Viso 2004).’ 13

similar idea to Meme McDonald’s desire to view the impressions left on the walking circles by the event and, specifically, the walkers’ footprints.

o Mary O’Neill’s art is an act of mourning – exploring art os Felix Ganzalez Torres, Dadang Christanto, Zoe Leonard

Shape-shifting, sweeping, decan and the fugitive

- Ephemeral art works are active – changing with time. “A ritually prepared object releases power as it decays” 13

- Briefly outlines the other articles in the publication – says that in all the articles “the ephemeral amplifies the present by giving it a temporal frame. ” 13

Purpura, Allyson (2009), ‘Framing the Ephemeral’, Introduction to a special issue: Ephemeral Arts I, 42 (3), 11-15.

Pertinence to M~M

M~M was an ephemeral arts event. The walking circles, and most of the artefacts they contained were not permanent objects. Article outlines a little of the history, as well as the rise of ‘conserved art’ as a commodity in galleries, and for trade.

Useful information about artists for further research.

Oscar Munoz paints with water on hot concrete. The portraits are of people who have disappeared in oppressive South American regimes. The faces, like the lives, disappear without trace.

Night walk and Shell Heading photos ready to print

Large multi-photo files are made for large format printing in the Deakin photo lab. The paper is 110cm wide. Cost is $1.50 per inch. A compromise must be made between large format photographs and total cost. In the end, the night photographs are printed at 50 cm on the long side, and the Shell Heading photos at 25 cm on the shorter side.

The Rock, Steampacket and Point Lonsdale – photoshop playtime

- The Big Rock Walking Circle

- Steampacket Place – towards Shell

- Point Lonsdale – towards Shell

This is just the beginning of creativity using Photoshop.